Symphony in D major for two violins, violas, basso, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets and timpani. Composed 1778.

Written in Paris for performance at the Concert spirituel, the genesis and first performance on 18 June 1778 of Mozart’s symphony is described in letters to his father of 12 June and 3 July:

[12 June 1778:] I . . . have just finished [a symphony] . . . which the Concert spiritual will open at Corpus Christi. . . I too am quite pleased with it. But I cannot say whether it will be popular—and, to tell the truth, I care very little, for who will not like it? I can answer for its pleasing the few intelligent French people who may be there—and as for the stupid one, I shall not consider it a great misfortune if they are not pleased. I still hope, however, that even asses will find something in it to admire—and, moreover, I have been careful not to neglect le premier coup d’archet—and that is quite sufficient. What a fuss the oxen here make of this trick! The devil take me if I can see any difference! They all begin together, just as they do in other places. It is really too much of a joke.

[3 July 1778:] I have had to compose a symphony for the opening of the Concert spiritual. It was performed on Corpus Christi day with great applause and I hear, too, that there was a notice about it in the Courier de L’Europe—so it has given great satisfaction. I was very nervous at the rehearsal for never in my life have I heard a worse performance. You have no idea how they twice scraped and scrambled through it. I was really in a terrible way and would gladly have had it rehearsed again but as there was so much else to rehearse, there was no time left. So I had to go to bed with an aching heart and in a discontented and angry frame of mind. I decided the next morning not to go to the concert at all; but in the evening, the weather being fine, I at last made up my mind to go, determined that if my symphony went as badly as it did in rehearsal, I would certainly make my way into the orchestra, snatch the fiddle out of the hands of Lahousaye, the first violin, and conduct myself! I prayed God that it might go well for it is all to His greater honour and glory; and behold—the symphony began. Raaff was standing beside me and just in the middle of the first allegro there was a passage which I felt sure must please. The audience were quite carried away—and there was a tremendous burst of applause. . . The andante also found favour, but particularly the last allegro because, having observed that all last as well as first allegros begin here with all the instruments playing together and generally unison, I began mine with two violins only, piano for the first eight bars— followed instantly by a forte. The audience, as I expected, said ‘hush’ at the soft beginning, and when they heard the forte, began at once to clap their hands. I was so happy that as soon as the symphony was over, I went off to the Palais Royale where I had a large ice, said the rosary as I had vowed to do—and went home.

The notice Mozart refers to, in the Courier de L’Europe (published in London), appeared in the 26 June issue: ‘The Concert Spirituel on Corpus Christi Day began with a symphony by M. Mozart. This artist, who from the tenderest age made a name for himself among harpsichord players, may today be ranked among the most able composers’.

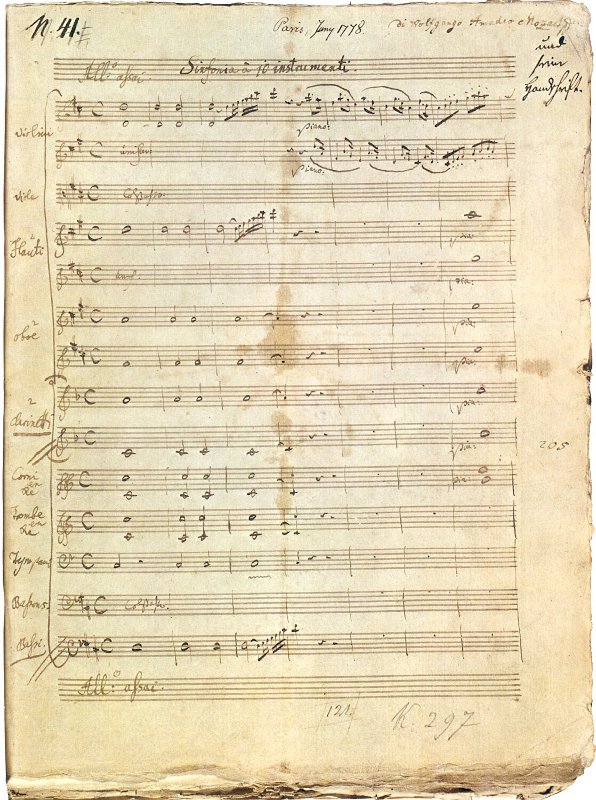

Mozart K297 ("Paris" Symphony) first page

The ‘Paris’ symphony was performed again on 15 August, the Feast of the Assumption, with a newly-composed Andante, as Mozart described in a letter to Leopold of 9 July:

[9 July 1778:] ...the symphony was highly approved of—and Le Gros [director of the Concert spiritual] is so pleased with it that he says it is his very best symphony. But the andante has not had the good fortune to win his approval. He declares that it has too many modulations and that it is too long. He derives this opinion, however, from the fact that the audience forgot to clap their hands as loudly and to shout as much as they did at the end of the first and last movements. For indeed the andante is a great favourite of mine and with all connoisseurs, lovers of music and the majority of those who have heard it. It is just the reverse of what Le Gros says—for it is quite simple and short. But in order to satisfy him (and, as he maintains, some others) I have composed a fresh andante—each good in its own way—for each has a different character. But the last pleases me even more.